Why did the crab cross the road? 🦀🚶🔦

In this issue: coming face to face with Bermuda's rarest crab

Travelling west along South Road at night makes me worry about only one thing: being hit in the face by a roach on the way home, especially on humid summer evenings.

But this week, the late summer brought a different kind of night time wanderer. Travelling through that stretch of road at the bottom of Botanical Gardens where tall trees make an arch overhead, the headlights from my moped illuminated an unmistakable shape: a large crab ambling down the road.

Too big to be a red land crab. It could only be one thing: a white, or giant land crab (Cardisoma guanhumi) - Bermuda’s rarest crab.

I pulled in to a bus lay-by, turned around and parked. I rushed towards where I saw the crab, worried it would be run over by the time I could get to it. There are no sidewalks here and vehicles speed down the long, straight road.

As I neared the spot where I saw the crab, a moped pulled over in front of me. He had seen the crab, too! And I started gesturing wildly to him. He looked at me, “are you okay?” he demanded. I realised how I looked, speed walking down a busy road, bike helmet in hand. He must have thought I had just gotten into an accident, or was fleeing some kind of dangerous situation! I explained to him I was helping a crab but I’m not sure if he really understood… He drove off.

Then I saw the crab. When it noticed me it started to edge sideways - more into the busy road - I carefully herded it in, so it was forced to the safer side. It promptly climbed over the low stone wall and fell ungracefully into botanical gardens.

What could I do? Now I was on the side of a busy road staring down a crab. And I knew if I moved he would surely launch himself into the road again. Luckily, I knew just the person to call - my friend Sammy who had worked with crabs before.

In minutes she was there, with her heavy duty gloves and a headlamp. While I held the light, she gnabbed the crab in one smooth motion. She had worked with red land crabs and white land crabs in the Bahamas and knew how to pick them up without getting ‘bitten.’ She crossed the crab’s claws over each other and carried the whole thing like a purse back to the car.

Something interesting Sammy told me is it’s not the white land crab’s impressive big claw that you have to watch out for - it’s actually the small one! The big claw is so big that your fingers will simply slip through when it’s closed. The small one, however, can pack a punch, and you don’t want to get your fingers caught between it.

Sammy quickly determined the crab was male - its abdomen was in a triangular shape rather than a circular one. I expected the crab to be female because females have to travel from their burrows that might be more inshore, to the ocean to release their eggs. Why would this male be so far away from where he was supposed to be? Sammy suggested he may be on the prowl for females. I also read that males who lose a fight over a burrow location are sometimes forced inshore by the victor.

Look at this thing! It’s big - but it’s far from the maximum size for a white land crab. The carapace (not including legs) can be up to 6 inches long! White land crabs are now rare in Bermuda, limited to a small number of areas that meet their habitat requirements, including Hungry Bay, Wreck Road, and Stocks Harbour. The crabs make their burrows in coastal mud or below mangroves, digging deep enough to maintain a pool of saltwater at the bottom so they can wet their gills. The crabs are scavengers, eating carrion and microorganisms on leaf litter as well as coastal plants like mangroves and grasses. There is a DENR conservation plan for this crab which is full of great local information.

South Road isn’t the spot for a crab - the road is full of dangerous traffic, and it’s so far away from the ocean that the crab was liable to suffocate. We knew we had to return the crab to suitable habitat, and Hungry Bay was the perfect spot - the largest remaining mangrove swamp in Bermuda. After a short ride in the car (the crab’s first I imagine) we reached the east side of the Hungry Bay mangrove swamp.

No sooner had we stepped out of the car than we heard some characteristic rustling - and there before us was another land crab! Seeing my first one tonight was enough excitement for me - but these woods were alive with white land crabs! We saw 5+ more in a short walk on the edge of the mangroves. Our original captive was happy to finally be let free:

Seeing a haven for these creatures, which I had always dreamed of seeing but had never seen in person until tonight, was a joy. It’s rare to see an abundance of species like this these days, and when you encounter it, it fills you with hope - something we are in need of in the midst of a triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. It also felt like a stirring follow up to my encounters with red land crabs and a land hermit crab last week - the universe is evidently delivering crabs to me at the moment. What does it mean?

These crabs are cantankerous and bumbling. Crustaceans can sometimes make people feel jumpy - they are arthropods, and occasionally look a bit like their cousins the spiders. But I had the opposite feeling about giant land crabs. They move unexpectedly slowly, and sometimes appear not to be able to control their bodies very well - a consequence of being so large, supported only by the scaled up version of insect legs. They are actually quite funny to watch - from seeing our crab Sunday-strolling on the main road, to seeing others in the Hungry Bay mangroves very noisily and conspicuously trudging over crisp, dry palmetto leaves - including one baring its claw at us as if to say ‘no pictures, please.’

Why are white land crabs so rare nowadays? A combination of factors. The largest contributor to their decline is probably the loss of their mangrove homes to development, pollution, and coastal erosion fuelled by climate change. Only recently have Bermudians begun to value and protect our mangroves as the havens of biodiversity they are. There has been some great news for Hungry Bay mangroves recently - with funds from the BZS and donations of time and materials from local people and businesses, DENR and local residents constructed a seawall to help stop storm surges from continuing to batter the mangrove perimeter and widen a gap in the forest.

Red and white land crabs are considered pests by gardeners and farmers throughout their range, digging conspicuous burrows in soil wherever they go. In the 1950s the Department of Agriculture responded to an exploding red land crab population by making cheap poison bait available to all Bermudians. The rest is history - we know that red land crabs are significantly diminished from a combination of poison, and the introduction of a predator - the yellow crowned night heron. White land crabs probably inadvertently ate the poison too, which reduced their numbers. Finally - invasive species like cats, rats and dogs can threaten the crabs, too - and navigating their way over our busy roads can be a death sentence during their migrations to the coast for spawning.

White land crabs are protected under the Protected Species Act 2003 in Bermuda. In other locations, they are an important food source and harvested for human consumption.

In this whole adventure, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the BAMZ Natural History Museum habitats room. I must have spent hours in there as a child, examining each diorama and finding all the tiny details. I was always impressed by the giant land crab, frozen mid claw-shake in the ‘Mangrove’ display - always hoping that I might somehow come across one in the nature reserves I loved so much, but resigned to the fact that it was more like the fluffy cahow chick in the ‘Upland forest’ display - a relic of the past, something that may never exist in its original range on the island, something that to encounter would be very unlikely, and very special. I’m happy to say that I have been able to see both a cahow, and now a giant land crab, in the pockets of Bermuda where those species still exist - and that wonder I felt, even just observing their models in BAMZ as a child, has never left me!

For the period September 11-25, 2024

I’m happy to report that I’ve seen some more golden Sargassum on our shores this week - only I keep getting to it too late to find much in it! The long summer of no Sargassum is over - and we may see a little more in autumn and especially in spring.

A few notable finds: the claw of a ghost crab - always fun to find! A sea whip, which I’ve rarely seen washed up, a sea heart (a kind of drift seed), a questionable knife, and a strange chunk of some kind of ocean going fish.

Something else I always love to find are crab carapaces - this is Plagusia depressa, inconspicuous and less commonly found than the sally lightfoot. The patterns on their shells are beautifully intricate. I find this is the case with lots of crustaceans, but you can only see it observing carapaces - as the real thing moves away too quickly for you to really look closely.

A clay pipe bowl - with ‘DUBLIN’ on the side. It’s always fun to find bits of pipe. Parts of the stem are more common, intact bowls a little less common, and entire pipes the most prized find of all. The shape, size, and and inscriptions on clay pipes can help you date them. Pipes can be found in Bermuda dating from about the 1600s to the 1800s. Dating pipes can get a little complex - but in general, pipe bowls got larger as tobacco got cheaper over time, and the pipes got thinner as more precise technology was available to make them. This one with its fancy inscription makes me think it’s a little more recent.

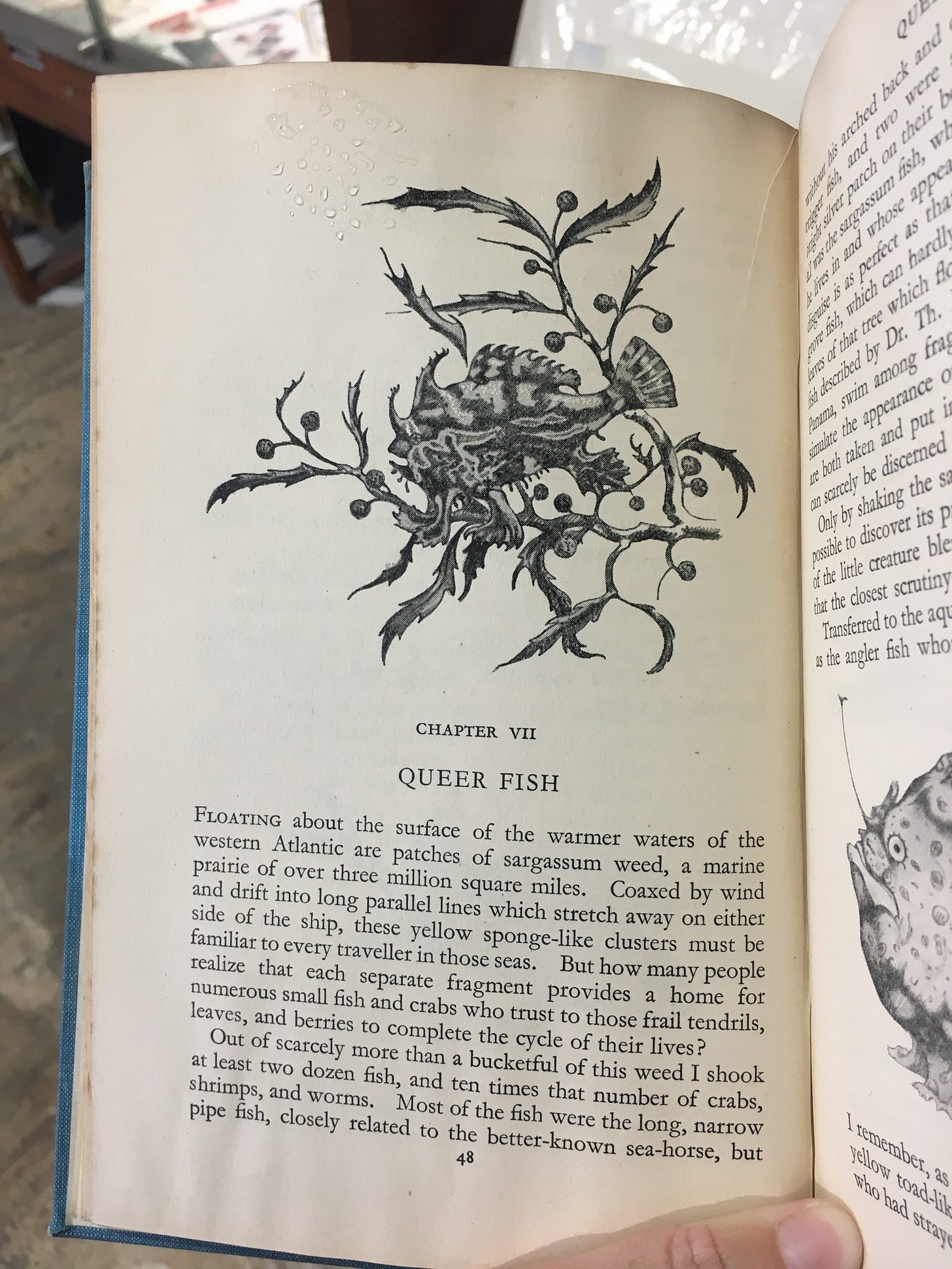

This week I wanted to feature some writing about Bermuda’s ocean that I found in a historical Bermuda book. This writer, too, found himself enamoured by the strange Sargassum fish. I particularly like the remarks about lots of fish and invertebrates dropping out of Sargassum when shaken! And the start of describing the vicious predation activities of the Sargassum fish. Its scientific name is Histrio histrio - and I’ve heard a naturalist say it’s called that because, anything you put in a tank with a Sargassum fish… it’s history!

Are you a beachcomber, mudlarker, or outdoors explorer? I would love to have your submissions of things you’ve found on the beach, or wildlife encounters for this ‘Guest Appearances’ section! Message me here or on Instagram to make a submission.

Thanks for reading, and join me next time for more beach bum activities.

Where to find me:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sargassogirl/

Website: http://www.sargassogirl.com/

Etsy: www.etsy.com/shop/SargassoGirl